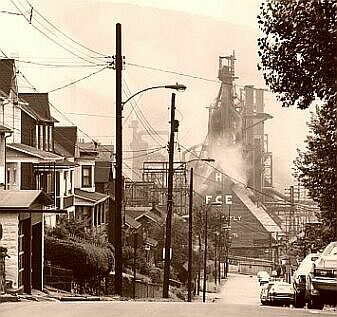

The song "Hard Times Cotton Mill Girls," as sung by Hedy West, kept running through my head as I read Tiffany Baker's Mercy Snow. The author describes the bleak, gritty atmosphere of New England company towns so vividly that this mean town on the banks of the toxic Androscoggin River becomes a major character.

Titan Mills, New Hampshire, is named for the paper mill owned and run by several generations of McAllisters. June McAllister, wife of the current owner, is by default the social leader of the town, despite her private misgivings. Born a poor girl in Florida, she has struggled to live up to her husband's privileged position in the town. She and Cal have one son, Nate, now 17 years old.

Titan Mills, New Hampshire, is named for the paper mill owned and run by several generations of McAllisters. June McAllister, wife of the current owner, is by default the social leader of the town, despite her private misgivings. Born a poor girl in Florida, she has struggled to live up to her husband's privileged position in the town. She and Cal have one son, Nate, now 17 years old.Mercy Snow's life has been about as far from privileged as one can get. Her family owned a small farm outside of town on the Androscoggin, downstream from where the mill pumped its heavy load of poisons into the river. When her mother dies, she and brother Zeke and younger sister Hannah return in a rusty motor home in search of their father. Pruitt has died and the farmhouse fallen to ruin, but no one cares or questions. At just age 17, Mercy has already become the responsible adult, caring for Zeke and Hannah.

A few weeks after their return, the local school bus, full of children, is forced off the aptly-named Devil's Slide Road into a ravine by a car in a hurry. Young Suzie Flyte is killed. The bus driver is put into a coma, and several other children are severely injured. When Zeke Snow's old truck is found a few hundred yards ahead, smashed into a tree, no one looks further for the culprit. Rescuers pulling the children out of the ravine also discover what seem to be the remains of Gert Snow, the children's grandmother, who had vanished many years ago––run away, it had been presumed. As far as Titan Falls is concerned, the Snows have always been a scandal, outcasts, and general bad news.

A few weeks after their return, the local school bus, full of children, is forced off the aptly-named Devil's Slide Road into a ravine by a car in a hurry. Young Suzie Flyte is killed. The bus driver is put into a coma, and several other children are severely injured. When Zeke Snow's old truck is found a few hundred yards ahead, smashed into a tree, no one looks further for the culprit. Rescuers pulling the children out of the ravine also discover what seem to be the remains of Gert Snow, the children's grandmother, who had vanished many years ago––run away, it had been presumed. As far as Titan Falls is concerned, the Snows have always been a scandal, outcasts, and general bad news.Zeke, questioned by the sheriff, flees in panic after assuring Mercy of his innocence. He had been imprisoned once for trying to protect her from rapists, and can't bear the thought of going to prison again. A skilled woodsman, he can hide out in the woods for months. Mercy is determined to prove his innocence, but is thwarted everywhere by her skeptical neighbors and June McAllister, who has unhappily discovered her own reasons to want Zeke convicted and the case closed.

There is not a lot of mystery in this story; the who is pretty apparent early on. It is more of a brooding, gothic suspense tale with an unhealthy dose of class differences. In small towns turned in on themselves for generations, the residents can become as mean and narrow as the streets they inhabit. Both Mercy and June are trying desperately to protect their families, but their differing resources make the contest ludicrously uneven.

There is not a lot of mystery in this story; the who is pretty apparent early on. It is more of a brooding, gothic suspense tale with an unhealthy dose of class differences. In small towns turned in on themselves for generations, the residents can become as mean and narrow as the streets they inhabit. Both Mercy and June are trying desperately to protect their families, but their differing resources make the contest ludicrously uneven. As the book closes, June is reading to a group of children in a library. She muses:

"The children knew only the panoramic and exaggerated villains of cartoons and video games…. But real badness wasn't like that. It masked itself in the faces of the people you loved, arrived in the form of accidents and misunderstandings, paraded through your life on quiet wheels before it exploded everything at once."

What disturbed me about this book was not the arrogance of privilege––that I expected. But the silent, mean-spirited complicity of the weak; the toadying sheriff and serpent-tongued townspeople, has haunted me. This, rather than the impossible small-town nightmares enumerated in so many gothic horror novels, troubled me and kept me reading. A remarkable book, beautifully written and depressing as hell. Read it anyway, and then examine your own conscience. I'm still working on mine.

What disturbed me about this book was not the arrogance of privilege––that I expected. But the silent, mean-spirited complicity of the weak; the toadying sheriff and serpent-tongued townspeople, has haunted me. This, rather than the impossible small-town nightmares enumerated in so many gothic horror novels, troubled me and kept me reading. A remarkable book, beautifully written and depressing as hell. Read it anyway, and then examine your own conscience. I'm still working on mine.Note: I received a free review copy of this book, published by Grand Central/Hachette Book Group, in January 2014.

This sounds like an uncomfortable book, and no easy read. Gossip and hatefulness are the ways that miserable people pin the blame, contempt, and fault on their perceived scapegoats. Surely, they can't be responsible for the misery in their lives, it is someone else's fault. When it's written as clearly and 'in living color' as it is in Mercy Snow, it's like pulling back a blanket to reveal a mass of writhing insects: a massive surprise that you want to get a fair bit of distance between you and it, and you're going to look at blankets with an extremely wary eye for a while.

ReplyDeleteBleagh. I'm going back to my tea and cookies, and go read the Secret Garden three times in a row.