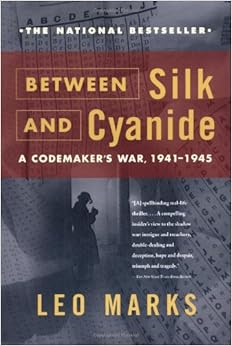

Leo Marks was the son of the proprietor of the London antiquarian bookstore, Marks & Co., at 84 Charing Cross Road. Yes, that's the eponymous bookstore made famous by Helene Hanff's book and the movie starring Anne Bancroft and Anthony Hopkins. Marks's introduction to cryptography came when, at age eight, he read Edgar Allen Poe's The Gold Bug and, fascinated by its description of a coded message leading to a buried treasure, he quickly broke the code behind the penciled letter notations inside the book covers that told the staff how much they'd paid for each book.

Once the Nazis overran Europe in 1940, Prime Minister Winston Churchill realized that the British would have to take the fight behind enemy lines. Churchill created the Special Operations Executive, whose brief was to "set Europe ablaze." SOE agents were fluent speakers of the languages of the occupied countries, and they infiltrated the Low Countries, France and Norway to help the local resistance, sabotage the German war effort and gather information to transmit back to Britain in code.

After writing to every agency he could think of and lobbying every possible influential contact, Leo Marks was accepted to cryptography school in 1941. His youth (he was just 21), flippancy and, perhaps, his Judaism, meant that after his training, he was not sent off to Bletchley Park with the rest of his class. Instead, he was sent to the new SOE, thought by some to be a collection of misfits. He soon learned that the life expectancy of an agent was poor, especially if the agent transmitted radio communications back to England. Germans patrolled with radio interception trucks to triangulate signals and find agents in the act of transmission; anyone could be stopped and searched at any time and might be found with coding paper on them. There were so many ways of getting caught, and capture meant certain torture, followed by execution or a trip to a prison camp where death was more than likely. No wonder the agents' standard kit included a cyanide pill.

On his first day at the SOE code room, Marks discovered that the main coding system in effect for agents was for them to use a poem as the key to code their messages. SOE knew each agent's poem and could decode the message. One problem with this system was that the codes used poetry well-known to anyone, including Germans, and that poem codes required messages to be lengthy. Another was that an agent under pressure might make a mistake, rendering his message an "indecipherable." That wasn't hard to understand, given how a poem was converted into a code. The agent had to choose five words from the poem, convert each letter in those words to a number, using a prescribed system, then use those numbers as the cipher to encode his or her message, beginning the message with an indicator to tell HQ which five words from the poem were being used. Standard operating procedure at SOE was to tell the agent who'd transmitted an indecipherable to re-send the message.

On his first day at the SOE code room, Marks discovered that the main coding system in effect for agents was for them to use a poem as the key to code their messages. SOE knew each agent's poem and could decode the message. One problem with this system was that the codes used poetry well-known to anyone, including Germans, and that poem codes required messages to be lengthy. Another was that an agent under pressure might make a mistake, rendering his message an "indecipherable." That wasn't hard to understand, given how a poem was converted into a code. The agent had to choose five words from the poem, convert each letter in those words to a number, using a prescribed system, then use those numbers as the cipher to encode his or her message, beginning the message with an indicator to tell HQ which five words from the poem were being used. Standard operating procedure at SOE was to tell the agent who'd transmitted an indecipherable to re-send the message.Young Leo was appalled. Poem codes were insecure and contributed to indecipherables. Requiring retransmission wasn't the answer. "Squads of girls must be specially trained to break agents' indecipherables. Records must be kept of the mistakes agents made in training––they might be repeating them in the field. . . . There must be no such thing as an agent's indecipherable."

Marks's war was with SOE bureaucracy as much as the Axis. Chain of command was reluctant to change any of its practices––especially on the say-so of a smart-mouthed 22-year-old working his first real job. But by buttonholing agents and sly insubordination, he managed slowly to introduce changes. Poem codes were largely replaced with one-time cipher pads printed on silk, which could be placed inside the lining of a coat and wouldn't rustle like paper if the agent was patted down by the enemy.

Marks's war was with SOE bureaucracy as much as the Axis. Chain of command was reluctant to change any of its practices––especially on the say-so of a smart-mouthed 22-year-old working his first real job. But by buttonholing agents and sly insubordination, he managed slowly to introduce changes. Poem codes were largely replaced with one-time cipher pads printed on silk, which could be placed inside the lining of a coat and wouldn't rustle like paper if the agent was patted down by the enemy.Though Marks was constitutionally unable to get along with the authorities in the SOE (he was called "not SOE-minded," though nobody could explain exactly what it meant to be SOE-minded), all of that disappeared when he worked with the "squads of girls" battling to decode indecipherables and, even more so, when he prepared agents about to be dropped behind enemy lines.

|

| Yeo-Thomas |

Female agents were indispensable in the occupied countries. Young men were often rounded up for forced labor, but women were not. They traveled relatively freely, could hide messages and weapons in their shopping baskets or under their skirts, and could get away with so much, simply because the Germans didn't tend to suspect them. Sixty women became agents in the SOE during World War II, and of the 39 who were dropped into France by parachute or fishing boat, 18 were captured, of whom only three survived. Marks trained some of the women who have become most well-known in the years following the war, including Violette Szabo and Noor Inayat Khan.

|

| Violette Szabo |

|

| Noor Inayat Khan |

After several weeks, she was betrayed and captured by the Gestapo. Despite her reputation as gentle and unworldly, she fought her captors like a tiger and twice briefly escaped from Gestapo headquarters on the Avenue Foch. She was shackled as a dangerous prisoner and brutal interrogations continued, but Noor is not known to have given any information to the Gestapo. She was transferred to a German prison and later to Dachau, where she and three other women from the SOE were executed on September 13, 1944. Noor was posthumously awarded the George Cross. For more about her, read Shrabani Basu's Spy Princess: The Life of Noor Inayat Khan, or watch the recent documentary, Enemy of the Reich, narrated by Helen Mirren (see the documentary's website here).

Marks's book was embargoed by the British government for over 10 years before it was finally published in 1998. If you have an interest in World War II espionage, cryptography, or just a gripping and well-told story of human behavior under pressure, please give it a try. I just hope my book club members feel the way I do about it.

|

| The poem that Leo Marks gave to Violette Szabo |

No comments:

Post a Comment