OD-ing can happen to you. For example, Harry Bosch and Harry Hole are wonderful, but too much of their company day after day, and they become those dinner guests who have forgotten how to go home. Or, take the case of reading a lot in the same subgenre. By the time you get to the seventh straight book of espionage, it's like eating nothing but pizza for a week.

OD-ing can happen to you. For example, Harry Bosch and Harry Hole are wonderful, but too much of their company day after day, and they become those dinner guests who have forgotten how to go home. Or, take the case of reading a lot in the same subgenre. By the time you get to the seventh straight book of espionage, it's like eating nothing but pizza for a week.It's good to cleanse your reading palate. Read something different from your usual fare. No matter what you commonly serve yourself, you can't go wrong with one of the two books below. They're different, period.

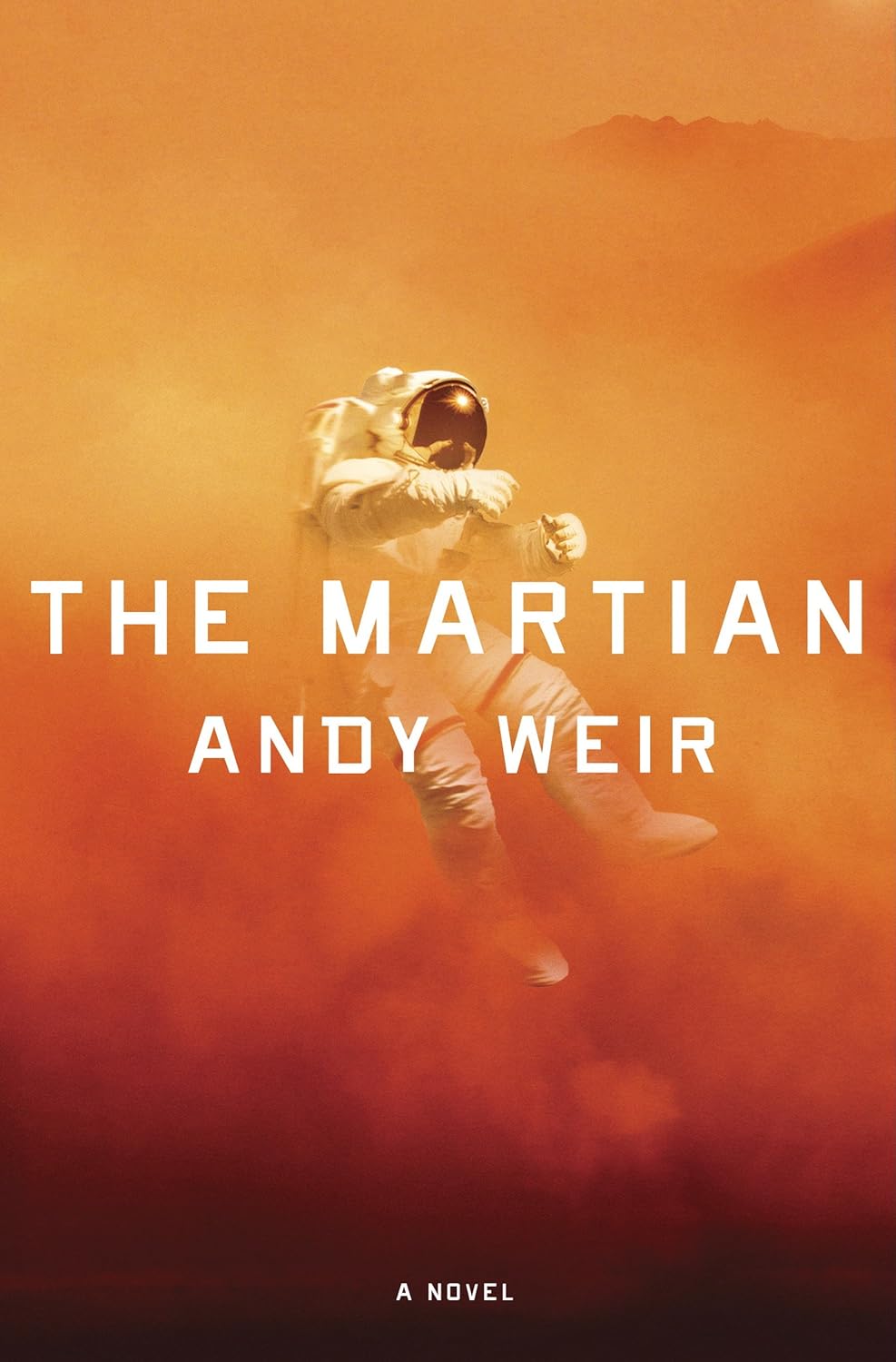

Calling all geeks: your ship has come in. But science-phobic people who scratch their heads at the idea that water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen can still enjoy The Martian by Andy Weir (Crown, February 2014). You can even skim the scientific details and get the gist, but I hope you don't. Weir, a long-time outer space aficionado, explains it very clearly. I know already this will be one of my favorite books this year.

Calling all geeks: your ship has come in. But science-phobic people who scratch their heads at the idea that water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen can still enjoy The Martian by Andy Weir (Crown, February 2014). You can even skim the scientific details and get the gist, but I hope you don't. Weir, a long-time outer space aficionado, explains it very clearly. I know already this will be one of my favorite books this year.In a nutshell, it's about astronaut Mark Watney's quest to remain alive after his Ares 3 crewmates, who believe he's dead, abandon him on Mars without any means of communication. Mark is a botanist, a mechanical engineer, and a Mr. Fix-It. He's also blessed with a terrific sense of black humor and determination to survive. He'll need both, as he'll run out of food and water long before the next mission to Mars arrives in four years. We read the journal entries (beginning with "I'm pretty much fucked"), in which Mark records his goals, games out how he'll overcome the problems involved, and then explains why those efforts failed and what he'll try next. It's fascinating to read about NASA's back-up systems in the Hab and rover and to watch Mark go about his jerry-rigging, which never becomes repetitious. I became attached to this inventive and likable astronaut and laughed as he breaks up the water making and farming with droll comments about his crewmates' love of 1970s TV and disco music. Mark is just so darn human.

|

| Russia recently brought back mice and newts from an orbit around Mars (Getty photo) |

Speaking of out of this world, maybe you saw the recent Washington Post article about the discovery of dinosaur fossils at the Hell Creek Formation in North and South Dakota. The fossils form a picture of "a freakish, birdlike species of dinosaur—11 feet long, 500 pounds, with a beak, no teeth, a bony crest atop its head, murderous claws, prize-fighter arms, spindly legs, a thin tail and feathers sprouting all over the place."

This "Chicken from Hell" would delight Prof. Lars Helland and Dr. Erik Tybjerg at the University of Copenhagen in S. J. Gazan's The Dinosaur Feather (trans. from the Danish by Charlotte Barslund, Quercus, 2013). It would also thrill Canada's top scientific magazine editor, Jack Jarvis, but it would enrage his old friend, University of British Columbia paleo-ornithologist Dr. Clive Freeman. These men are combatants in a debate that has engaged scientists for 150 years: are birds present-day dinosaurs or do they originate from an even earlier primitive reptile?

Sifting through the arguments about this question is Anna Bella Nor, a single mother who's frantically writing her master of science dissertation at the University of Copenhagen. She's always full of rage. Her three-year-old daughter, Lily, is a handful. Anna isn't on the best of terms currently with her parents, and she has no time for her old friends. Anna loathes her dissertation supervisor, Prof. Helland, for being unavailable and impossible to talk to when he is available. Recently, he has been looking and acting very strange. When he's found dead, sprawled in his office reclining chair, his severed tongue on his lap, it barely grieves Anna, who now must depend on the guidance of the reclusive Dr. Tybjerg, who disappears into the University's Natural History Museum, and her office-mate, Johannes Trøjborg, who looks weird and is weird, albeit kind. She barely has time for "the World's Most Irritating Detective," Søren Marhauge, Denmark's youngest police superintendent.

Sifting through the arguments about this question is Anna Bella Nor, a single mother who's frantically writing her master of science dissertation at the University of Copenhagen. She's always full of rage. Her three-year-old daughter, Lily, is a handful. Anna isn't on the best of terms currently with her parents, and she has no time for her old friends. Anna loathes her dissertation supervisor, Prof. Helland, for being unavailable and impossible to talk to when he is available. Recently, he has been looking and acting very strange. When he's found dead, sprawled in his office reclining chair, his severed tongue on his lap, it barely grieves Anna, who now must depend on the guidance of the reclusive Dr. Tybjerg, who disappears into the University's Natural History Museum, and her office-mate, Johannes Trøjborg, who looks weird and is weird, albeit kind. She barely has time for "the World's Most Irritating Detective," Søren Marhauge, Denmark's youngest police superintendent. Søren is 37 years old, and "he could identify a murderer from the mere twitching of a single, out-of-place eyebrow hair, he could knit backward, and everyone he had ever loved had died and left him behind." Although he has a perfect record for solving criminal cases, his losses have left Søren a big, unresolved mess. His long-term girlfriend, Vibe, has now married another man. At the same time Søren investigates Helland's murder—and, shortly thereafter, another death in this case—he finds himself investigating his own past in order to understand his unhappy present.

Søren is 37 years old, and "he could identify a murderer from the mere twitching of a single, out-of-place eyebrow hair, he could knit backward, and everyone he had ever loved had died and left him behind." Although he has a perfect record for solving criminal cases, his losses have left Søren a big, unresolved mess. His long-term girlfriend, Vibe, has now married another man. At the same time Søren investigates Helland's murder—and, shortly thereafter, another death in this case—he finds himself investigating his own past in order to understand his unhappy present. Joining him in parallel personal odysseys into the mysteries of their pasts are Johannes and Anna. Unlike these three Danes, Canadian scientists Jarvis and Freeman don't do their own digging; writer Gazan excavates their joint history for us. This makes for a very unusual book, in which everyone—detective, suspects, their connections, and the reader—is trying to figure out questions involving identity, in one form or another. In addition to this interesting "all-hands-on-deck" approach to various mystery investigations, Gazan, who earned a biology degree, serves up an incredibly fascinating scientific debate. Her experience in academia is reflected in the book characters' believability. They engage in a genuine scholarly search for information that's affected by their personal biases and professional jealousies, as they race to publish and defend their findings. I read this book at the suggestion of my fellow Material Witness, Periphera, who knew I'd appreciate Gazan's depiction of the forces that drive university research and politics, and the biological knowledge that gives her book some very unsettling moments and a highly unusual (thank goodness!) method of murder.

Joining him in parallel personal odysseys into the mysteries of their pasts are Johannes and Anna. Unlike these three Danes, Canadian scientists Jarvis and Freeman don't do their own digging; writer Gazan excavates their joint history for us. This makes for a very unusual book, in which everyone—detective, suspects, their connections, and the reader—is trying to figure out questions involving identity, in one form or another. In addition to this interesting "all-hands-on-deck" approach to various mystery investigations, Gazan, who earned a biology degree, serves up an incredibly fascinating scientific debate. Her experience in academia is reflected in the book characters' believability. They engage in a genuine scholarly search for information that's affected by their personal biases and professional jealousies, as they race to publish and defend their findings. I read this book at the suggestion of my fellow Material Witness, Periphera, who knew I'd appreciate Gazan's depiction of the forces that drive university research and politics, and the biological knowledge that gives her book some very unsettling moments and a highly unusual (thank goodness!) method of murder.So, take your pick of these two distinctive books. A yen for surviving in outer space or a look at the dinosaurs that walked the Earth long ago and still fly among us? Or don't choose between them: I highly recommend them both.

Georgette,

ReplyDeleteThe Martian sounds like a book to really titillate the imagination. Coincidently I am reading the Edgar Rice Burroughs Mars books featuring the adventures of John Carter the first of which was written in 1917. The Princess of Mars is on the table as we speak. What fun to contrast and compare the difference a century makes.

MC, I love the idea of reading books set on Mars that are separated by a century. I'm sure you'd enjoy Weir's THE MARTIAN. Astronaut Mark Watney is my ideal of the American man: warm, funny, smart, and can-do. I'm looking forward to the movie made of this book, and I hope Weir writes another one.

ReplyDelete