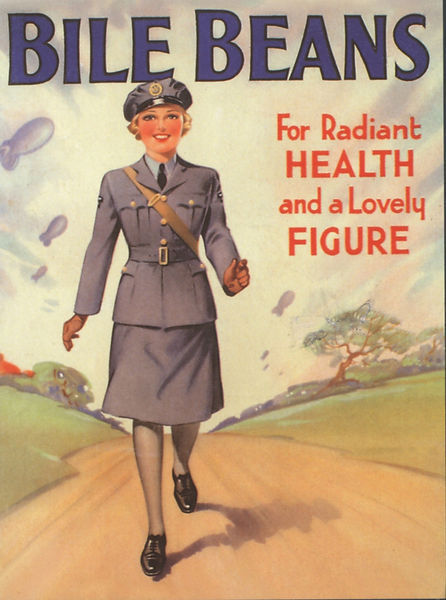

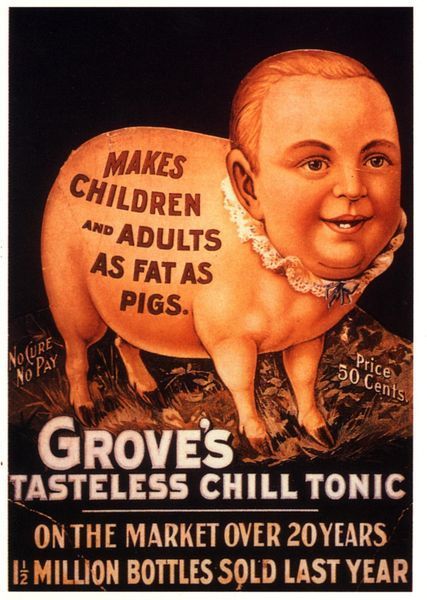

Back in the 1930s, before television, print advertising was focused on product packaging and illustrations in newspapers and buses. Slogans were the big thing. Advertising and marketing have come a long way since the 1930s, but when it comes to book marketing, there are still similarities. Most people choose a book from a dust jacket, a website product page or a catalog, which makes it necessary to give a quick impression, almost as with an old-fashioned billboard or ads on the side of a bus. However, a big difference between advertising a book and deodorant, for example, is that book marketers seem to want to make the book sound as much as possible like something that's already been done. No "new and improved" here!

Back in the 1930s, before television, print advertising was focused on product packaging and illustrations in newspapers and buses. Slogans were the big thing. Advertising and marketing have come a long way since the 1930s, but when it comes to book marketing, there are still similarities. Most people choose a book from a dust jacket, a website product page or a catalog, which makes it necessary to give a quick impression, almost as with an old-fashioned billboard or ads on the side of a bus. However, a big difference between advertising a book and deodorant, for example, is that book marketers seem to want to make the book sound as much as possible like something that's already been done. No "new and improved" here!

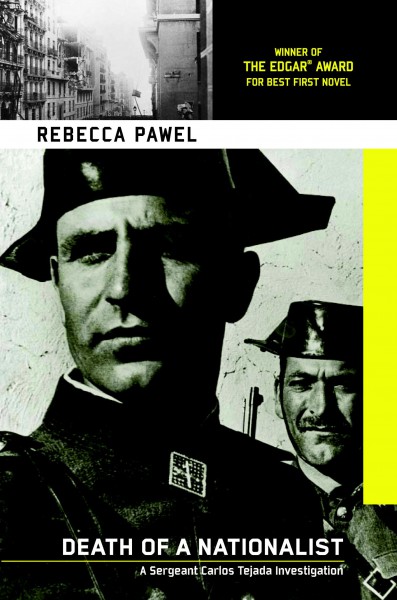

Remember back in 2003, when Dan Brown's The Da Vinci Code was a smash hit? For several years after that, every novel that had any element of conspiracy, suspense, religion, history or art was suddenly the "next Da Vinci Code." All I can say is that, thankfully, time has healed that particular wound.

I'm sure you know what phenomenon is coming next. Yes, it's the late Stieg Larsson's Millennium Trilogy. These books were a blessing and curse for Nordic crime fiction writers. On the plus side, Nordics were suddenly all the rage and writers were getting translated and sold like hot æbleskiver all over the world. The big negative, though, was that every Lars, Johan and even Karin had to see "the next Stieg Larsson" splashed in big letters over their books' dust jackets.

I've read that it annoyed Jo Nesbø no end (and rightfully so) to be called the next Stieg Larsson. He was smart enough not to say it publicly, but he's a far better writer than Larsson ever was. Not only that, but three of his Harry Hole books were already available in English when The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo came out. So that's marketing for you; don't let the facts get in the way.

Gillian Flynn's Gone Girl is another one of those books that every publicist wants to tell us has been duplicated in their publishing company's latest thriller. Random House says that Laura McHugh's The Weight of Blood, coming in March, is for fans of Gillian Flynn. Herman Koch's The Dinner is inexplicably described as a "European Gone Girl." At least A. S. A. Harrison's The Silent Wife, another marketer's doppelgänger for Gone Girl, has a plot involving a married couple, his-and-hers narratives and a murder.

That brings us to the latest marketing misdemeanor: Downton Abbey. Marketers for every book set within hound-sniffing distance of an English manor house are grabbing potential readers by the elbow to say that if they like Downton Abbey they'll just love this book here. I had this experience recently. I was looking around for an audiobook to accompany me on my long walks with the dog. I stumbled across Julianna Deering's Rules of Murder. The cover looked attractive, in a Golden-Age-of-Mystery way, and the reader was listed as being Simon Vance, one of the real gems of the profession.

That brings us to the latest marketing misdemeanor: Downton Abbey. Marketers for every book set within hound-sniffing distance of an English manor house are grabbing potential readers by the elbow to say that if they like Downton Abbey they'll just love this book here. I had this experience recently. I was looking around for an audiobook to accompany me on my long walks with the dog. I stumbled across Julianna Deering's Rules of Murder. The cover looked attractive, in a Golden-Age-of-Mystery way, and the reader was listed as being Simon Vance, one of the real gems of the profession.The bold-type marketing for the book said "Downton Abbey Meets Agatha Christie in this This Sparkling Mystery." (Don't ask me why the initial letters of those last three words are capitalized. It must be more marketing magic. Or should I say More Marketing Magic?) I have more than a little bit of cynicism in my nature, so I wasn't at all surprised that there wasn't a peer of the realm to be found, nor any below-stairs intrigue, and that the book's only resemblance to Downton Abbey was that a butler does make the occasional appearance.

As for Agatha Christie, well, I think Dame Agatha would be unamused by the comparison to her work. True, Rules of Murder is set in the 1930s and has a touch of young romance mixed with its detective work. But that's where the comparison runs out of petrol. Deering is a pen name, and I suspect the real author is an American who wrote the book with an American-to-British English dictionary at her elbow. I wish someone had told her that throwing in frequent "I say, old man" and "that's deuced peculiar" comments do not an English novel make.

Here's the really crazy part, though. It turns out that the book is Christian fiction. Absolutely nowhere in the marketing is there the slightest mention of that fact. I was reading about the two young romantic leads chatting at a party when all of a sudden, out of nowhere, the young woman starts talking about God and faith. I would have been completely taken aback, except for the fact that she'd just finished telling the male lead that adding champagne was a good way to ruin the taste of a perfectly good glass of orange juice. That was one clue that the "sparkling" part of the book's tag line was deceptive.

As far as I know, there are quite a few people interested in Christian fiction, so I'm puzzled why the marketers for this book would choose to keep that aspect of the book hidden. I think those marketers might be even more cynical than I am. They probably figured that these days a label of "Christian fiction," however accurate, wouldn't sell a book nearly as well as a false Downton Abbey blurb.

As far as I know, there are quite a few people interested in Christian fiction, so I'm puzzled why the marketers for this book would choose to keep that aspect of the book hidden. I think those marketers might be even more cynical than I am. They probably figured that these days a label of "Christian fiction," however accurate, wouldn't sell a book nearly as well as a false Downton Abbey blurb.

Lord Peter Wimsey, in his Death Bredon persona, observed that advertising's "essence is to tell plausible lies for money." In this case, the marketers should have focused a little more on the "plausible" part of that observation. Better yet, they might have marketed the book as what it actually is.

Here's to reading books that can't be––or at least aren't––marketed as being just like something else.

.jpg)