With all the winter titles I'm collecting, I feel like a chipmunk that doesn't know when to stop preparations. Hibernating would certainly be easier. I need creepy books for stormy nights and traditional mysteries for when I'm tired. Italian crime fiction for an excuse to rampage into the kitchen. Books for reading with a glass of red and others with a glass of white. My searching never stops, because sometimes it's hard to find the right book to read.

With all the winter titles I'm collecting, I feel like a chipmunk that doesn't know when to stop preparations. Hibernating would certainly be easier. I need creepy books for stormy nights and traditional mysteries for when I'm tired. Italian crime fiction for an excuse to rampage into the kitchen. Books for reading with a glass of red and others with a glass of white. My searching never stops, because sometimes it's hard to find the right book to read. Take, for example, an evening after I did nothing but spin my wheels at work. Suitable reading could be Kafkaesque or frothy P. G. Wodehouse. Good books of both these types are scarce, but I'm optimistic about Gene Wolfe's The Land Across (Tor, November 26, 2013). It involves nightmarish travel, no-escape authoritarianism, becoming a pawn in an elaborate game, espionage, and elements of The Twilight Zone.

Take, for example, an evening after I did nothing but spin my wheels at work. Suitable reading could be Kafkaesque or frothy P. G. Wodehouse. Good books of both these types are scarce, but I'm optimistic about Gene Wolfe's The Land Across (Tor, November 26, 2013). It involves nightmarish travel, no-escape authoritarianism, becoming a pawn in an elaborate game, espionage, and elements of The Twilight Zone.

The poor guy (or maybe not) trapped in this situation (or maybe not, you get what I mean?) is American travel writer Grafton, who enters an obscure Balkan country that has made itself nearly inaccessible. At the border, guards pull Grafton off the train, take his passport, and then arrest him for not having it. He's released into the private custody of Kleon, a thug with a beautiful wife, Martya. Kleon will be shot if their prisoner escapes, but Martya involves Grafton in a treasure hunt that leads him to be kidnapped by various groups, captured and jailed by the secret police, and involved in activities that make him (and the reader) wonder just which side Grafton wants to be on, or maybe already is on. Or something. About all this, I say, "Yeehaw!"

I've been partial to Russian writers since I was a little kid, fascinated by pictures of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in my dad's books. Mikhail Shishkin is considered one of Russia's best contemporary writers, and I'm leaping at the chance to read his The Light and the Dark (translated from the Russian by Andrew Bromfield, and available from Quercus on January 2, 2014), although, after reading several reviews, I remain in the dark about what the book is really about. I'll crawl into bed with it and a glass of Stoli after I get Frank Sinatra singing Strangers in the Night on the stereo.

I've been partial to Russian writers since I was a little kid, fascinated by pictures of Tolstoy and Dostoevsky in my dad's books. Mikhail Shishkin is considered one of Russia's best contemporary writers, and I'm leaping at the chance to read his The Light and the Dark (translated from the Russian by Andrew Bromfield, and available from Quercus on January 2, 2014), although, after reading several reviews, I remain in the dark about what the book is really about. I'll crawl into bed with it and a glass of Stoli after I get Frank Sinatra singing Strangers in the Night on the stereo.

Okay, I do know this: Vovka and Sashenka fell in love as teenagers, and both became medics. Sashenka remains in Russia, while Vovka has been sent with the army to China, where the Boxer Rebellion rages. They write to each other, and we learn about them through their separate narrations. Now it gets tricky. The book involves enough mysticism, allusions, metaphors, and legends to shake a stick at, and it's not clear from what I read whether Vovka and Sashenka are actually alive at the same time. Definitely, this is an intriguing book I must read.

After those two books, you might be wondering if I read only to confuse myself. I have a clearer understanding of this one, Orfeo (Norton, January 20, 2014), by Pulitzer finalist and National Book Award winner (for 2006's The Echo Maker) Richard Powers. I'll put it aside for a time I want to sink my mental teeth into a book, because it's a complex take on cybertechnology, the connections between music and science, and fear and governmental repression. It's an escape narrative, too.

After those two books, you might be wondering if I read only to confuse myself. I have a clearer understanding of this one, Orfeo (Norton, January 20, 2014), by Pulitzer finalist and National Book Award winner (for 2006's The Echo Maker) Richard Powers. I'll put it aside for a time I want to sink my mental teeth into a book, because it's a complex take on cybertechnology, the connections between music and science, and fear and governmental repression. It's an escape narrative, too.

In a nutshell: Peter Els, a 70-year-old divorced and retired avant-garde music composer, has a microbiology lab at home (don't we all?). There, he works as a "do-it-yourself genetic engineer" in efforts to "break free of time and hear the future." Els's dog, Fidelio, goes into cardiac arrest one day, and the people who respond to his 911 call spot the lab setup. Suddenly, Els is a suspected domestic bioterrorist and a Homeland Security fugitive, whose story goes viral. On the lam, Els ponders music and reflects on the life that got him into this mess.

Wow, Marcel Theroux's melancholy English scholar Nicholas Slopen could do some similar reflecting, given the predicament he gets himself into in Strange Bodies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 4, 2014). It begins when collector Hunter Gould asks him to authenticate papers thought to be the 18th-century work of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Slopen discovers something strange—he's sure the work is that of Johnson, but the paper is modern.

Wow, Marcel Theroux's melancholy English scholar Nicholas Slopen could do some similar reflecting, given the predicament he gets himself into in Strange Bodies (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, February 4, 2014). It begins when collector Hunter Gould asks him to authenticate papers thought to be the 18th-century work of Dr. Samuel Johnson. Slopen discovers something strange—he's sure the work is that of Johnson, but the paper is modern.

Don't tell me you don't see what this means: obviously, a live body has been invaded by the soul of a dead person. Events ensue and things for Slopen take a decided turn for the worse. Via an operation straight out of a horror flick, he becomes a tattooed, uh, ex-ex-convict. This acclaimed gothic tale, blending comedy with horror, sounds much too rich to resist on a dreary, rain-filled day.

And now for something completely different. I'd like to tell you about the new Det. Inspector Bill Slider book by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, Hard Going (Severn House, February 1, 2014).

And now for something completely different. I'd like to tell you about the new Det. Inspector Bill Slider book by Cynthia Harrod-Eagles, Hard Going (Severn House, February 1, 2014).

This is the 16th book of a character-driven British police procedural series known for its wry wit and wordplay (especially puns), music, and the repartee between Slider and his Shepherd's Bush CID colleagues. Unlike the common brand of troubled cop whose home life consists of falling asleep with a bottle in a chair in front of the TV, Slider has an entertaining relationship with his wife, Joanna, and kids.

In this latest case, Joanna is exasperated when Bill is called in on his day off to investigate the bludgeoning murder of Lionel Bygood, whose reputation for generosity and kindness may be cover for more sinister activities.

As crime fiction fans, we routinely come across characters who have done bad things. Some of these perpetrators earn a portion of the compassion usually reserved for their victims. I'm interested to see how first-time author James Scott examines morality in his story of Elspeth Howell, a deeply religious woman in late 19th-century upstate New York, who expects divine retribution for her crimes.

As crime fiction fans, we routinely come across characters who have done bad things. Some of these perpetrators earn a portion of the compassion usually reserved for their victims. I'm interested to see how first-time author James Scott examines morality in his story of Elspeth Howell, a deeply religious woman in late 19th-century upstate New York, who expects divine retribution for her crimes.

In Scott's The Kept (Harper/HarperCollins, January 7, 2014), Howell trudges home through a blizzard after her duties as a midwife have kept her away for a month. She is greeted by a grisly scene: her husband Jorah and four of her five children are murdered. Only 12-year-old Caleb is alive. Howell survives her accidental wounding by Caleb and his attempt to create a funeral pyre of the house. The two of them decide to track down the killers, whose motivation may be connected to Howell's compulsion to create a family (through abductions), when she and Jorah couldn't conceive children of their own.

After contemplating retribution and redemption, I'll be craving breakneck speed. Here's a book that might explode in my hands, it's so adrenaline-charged. Runner (Minotaur, February 18, 2014) is by Patrick Lee. Early readers rave, and Kirkus Reviews says, "With this book, he enters the ranks of the best action-thriller writers."

It begins with Sam Dryden, still grieving over the death of his wife and daughter, taking a midnight jog on a California beach. He literally runs into a panicky 12-year-old girl, fleeing from a group of heavily armed men. She knows her name is Rachel, she's been held against her will, and the men are trying to kill her because she can read minds. But that's all she remembers. Sam, a former Special Forces operative, is just the guy to help her play cat and mouse.

It begins with Sam Dryden, still grieving over the death of his wife and daughter, taking a midnight jog on a California beach. He literally runs into a panicky 12-year-old girl, fleeing from a group of heavily armed men. She knows her name is Rachel, she's been held against her will, and the men are trying to kill her because she can read minds. But that's all she remembers. Sam, a former Special Forces operative, is just the guy to help her play cat and mouse.

Robert Harris's Fatherland is a detective story set in an alternative history in which Nazi Germany won WWII. His latest sounds like the perfect winter weekend accompaniment to French-roast coffee and croissants. An Officer and a Spy (Knopf, January 28, 2014) is a thriller that Publishers Weekly calls "easily the best fictional treatment of the Dreyfus Affair yet." Harris's narrator and main character in this late-19th century French espionage case is Col. Georges Picquart of the French Army.

Robert Harris's Fatherland is a detective story set in an alternative history in which Nazi Germany won WWII. His latest sounds like the perfect winter weekend accompaniment to French-roast coffee and croissants. An Officer and a Spy (Knopf, January 28, 2014) is a thriller that Publishers Weekly calls "easily the best fictional treatment of the Dreyfus Affair yet." Harris's narrator and main character in this late-19th century French espionage case is Col. Georges Picquart of the French Army.

When Picquart is asked to head a counterespionage investigation of the Affair, he is already convinced of Alfred Dreyfus's guilt; however, his conviction fades as he finds contradictory physical evidence and suggestions that secrets continue being disclosed to Germany. His superiors and the public, inflamed by virulent anti-Semitic articles in the press, aren't interested in retrying the case. At great personal and professional risk, Picquart continues his search for the truth.

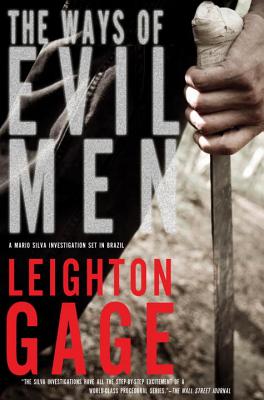

It's not easy finding a great hardboiled series featuring compelling, psychologically complex characters; an exotic setting; and a focus on social justice. It's also not easy finding an author as kind and generous as the late Leighton Gage (1942-2013). That's why it's bittersweet to see his seventh and last Mario Silva book, The Ways of Evil Men (Soho Crime, January 21, 2014), garner starred reviews.

I first met Chief Inspector Silva of the Brazilian Federal Police in 2007's Blood of the Wicked, but it's not necessary to start at this beginning of the series to enjoy Silva's investigations.

Here's his last case: After 39 members of the Awana tribe are found dead in the remote Brazilian state of Pará, National Indian Foundation agent Jade Calmon can't get local police to pay attention. Fighting breaks out over the valuable tribal reservation land. Calmon calls her childhood friend Mario, now Chief Inspector Silva. As usual, the incorruptible and decent Silva and his team pursue justice in a corrupt and unfair system.

I love international crime fiction, but there's a soft spot in my heart for deeply flawed characters who murder and are murdered in small-town America. At one time, I lived in a New Hampshire village, and I long for New Hampshire voices and landscape. I'll find them (and some magical realism) in Tiffany Baker's Mercy Snow (Grand Central, January 14, 2014).

I love international crime fiction, but there's a soft spot in my heart for deeply flawed characters who murder and are murdered in small-town America. At one time, I lived in a New Hampshire village, and I long for New Hampshire voices and landscape. I'll find them (and some magical realism) in Tiffany Baker's Mercy Snow (Grand Central, January 14, 2014).

It's the mid-1990s, and the orphaned Snow kids—19-year-old Mercy; her older brother, Zeke; and younger sister, Hannah—return to Titan Falls, New Hampshire, to claim their late father's land. Their family has a reputation for trouble, and trouble is what they get on the night before Thanksgiving, when a church youth-group bus goes off a cliff, killing one and putting the driver in a coma. Nearby, Zeke's pickup is found, crashed into a tree. Townspeople blame Zeke for the bus accident, but Mercy knows he's not responsible. Opposing her efforts to clear him are the McAllisters, who own the paper mill that employs most of Titan Falls.

It's not easy finding a great hardboiled series featuring compelling, psychologically complex characters; an exotic setting; and a focus on social justice. It's also not easy finding an author as kind and generous as the late Leighton Gage (1942-2013). That's why it's bittersweet to see his seventh and last Mario Silva book, The Ways of Evil Men (Soho Crime, January 21, 2014), garner starred reviews.

I first met Chief Inspector Silva of the Brazilian Federal Police in 2007's Blood of the Wicked, but it's not necessary to start at this beginning of the series to enjoy Silva's investigations.

Here's his last case: After 39 members of the Awana tribe are found dead in the remote Brazilian state of Pará, National Indian Foundation agent Jade Calmon can't get local police to pay attention. Fighting breaks out over the valuable tribal reservation land. Calmon calls her childhood friend Mario, now Chief Inspector Silva. As usual, the incorruptible and decent Silva and his team pursue justice in a corrupt and unfair system.

I love international crime fiction, but there's a soft spot in my heart for deeply flawed characters who murder and are murdered in small-town America. At one time, I lived in a New Hampshire village, and I long for New Hampshire voices and landscape. I'll find them (and some magical realism) in Tiffany Baker's Mercy Snow (Grand Central, January 14, 2014).

I love international crime fiction, but there's a soft spot in my heart for deeply flawed characters who murder and are murdered in small-town America. At one time, I lived in a New Hampshire village, and I long for New Hampshire voices and landscape. I'll find them (and some magical realism) in Tiffany Baker's Mercy Snow (Grand Central, January 14, 2014).It's the mid-1990s, and the orphaned Snow kids—19-year-old Mercy; her older brother, Zeke; and younger sister, Hannah—return to Titan Falls, New Hampshire, to claim their late father's land. Their family has a reputation for trouble, and trouble is what they get on the night before Thanksgiving, when a church youth-group bus goes off a cliff, killing one and putting the driver in a coma. Nearby, Zeke's pickup is found, crashed into a tree. Townspeople blame Zeke for the bus accident, but Mercy knows he's not responsible. Opposing her efforts to clear him are the McAllisters, who own the paper mill that employs most of Titan Falls.

I wish my German were up to reading Nele Neuhaus's series with Chief Superintendent (in German, the impressive-looking word "Kriminalhauptkommissar")

Oliver von Bodenstein and Detective Pia Kirchhoff, set in Germany's Taunus region. As often the case with translated crime fiction, these books are arriving in the US in a frustratingly willy-nilly way. Oh well, we'll take what we can get of this popular series.

I wish my German were up to reading Nele Neuhaus's series with Chief Superintendent (in German, the impressive-looking word "Kriminalhauptkommissar")

Oliver von Bodenstein and Detective Pia Kirchhoff, set in Germany's Taunus region. As often the case with translated crime fiction, these books are arriving in the US in a frustratingly willy-nilly way. Oh well, we'll take what we can get of this popular series.Bad Wolf (translated from the German by Steven T. Murray, St. Martin's/Minotaur, January 21, 2014) appears after last year's Snow White Must Die. It involves the murder investigation of an unidentified teenage girl, who washed up on the bank of the Main River outside Frankfurt. The crime may be linked to the rape of a TV reporter investigating a child welfare organization and pornography ring.

We all have our own idiosyncrasies. For whatever reason, some people just aren't fond of short stories. I like them. A lot. Here are a few wonderful upcoming collections:

The stories in Yu Hua's Boy in the Twilight: Stories of the Hidden China (translated

from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr, Pantheon, January 21, 2014) appear to be about ordinary people. "Their Son" is about a

hard-working father, who rides a crowded bus to work in a factory, so he can put his son

through college; the son casually spends money on taxis. That one hooked me on the book right there.

The stories in Yu Hua's Boy in the Twilight: Stories of the Hidden China (translated

from the Chinese by Allan H. Barr, Pantheon, January 21, 2014) appear to be about ordinary people. "Their Son" is about a

hard-working father, who rides a crowded bus to work in a factory, so he can put his son

through college; the son casually spends money on taxis. That one hooked me on the book right there. Autobiography of a Corpse was translated from the Russian by Joanne Turnbull and was published by New York Review Books on December 3, 2013. It's heartbreaking to learn that author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky wrote these gems in the '20s and '30s, and we're only now reading them. A couple: Human spite is an unlikely source of energy in "Yellow Coal"; a man's lifelong goal to bite his own elbow has surprising consequences in "The Unbitten Elbow."

Autobiography of a Corpse was translated from the Russian by Joanne Turnbull and was published by New York Review Books on December 3, 2013. It's heartbreaking to learn that author Sigizmund Krzhizhanovsky wrote these gems in the '20s and '30s, and we're only now reading them. A couple: Human spite is an unlikely source of energy in "Yellow Coal"; a man's lifelong goal to bite his own elbow has surprising consequences in "The Unbitten Elbow." Lorrie Moore is known for her wit and tragicomic short stories about people whom you'd swear are real. For example, in "The Juniper Tree," a teacher is forced to sing "The Star-Spangled Banner" when she's visited by the ghost of a recently deceased friend. This story is among those in Bark (Knopf, March 4, 2014), her first collection in 15 years.

Lorrie Moore is known for her wit and tragicomic short stories about people whom you'd swear are real. For example, in "The Juniper Tree," a teacher is forced to sing "The Star-Spangled Banner" when she's visited by the ghost of a recently deceased friend. This story is among those in Bark (Knopf, March 4, 2014), her first collection in 15 years. I hope you're finding plenty of books to keep you through the winter. Don't disappear, because tomorrow Periphera has more titles for you.

Oh Georgette, I have read a number of Gene Wolfe's books. They are haunting and often surreal. He is a very dense, painterly writer; I can envision scenes from his books even years later, as clearly as if from a movie.

ReplyDeletePeri, I'm very happy to hear this! I've heard of Gene Wolfe, but I've never gotten around to reading any of his books, and now I'll be sure to do that. THE LAND ACROSS sound very fun.

ReplyDelete