It turns out she was born Aline Griffith in Pearl River, in upstate New York. She was working as a model in New York City, but didn't drink or smoke, didn't go to clubs and wore saddle shoes and schoolgirl clothes when she took the bus to and from work.

Aline's younger brothers were serving in the armed forces during World War II and she complained that she wanted to be in the war, too, but hadn't been able to find her way in. At age 19, though, she complained to just the right person: the brother of a friend, who worked at the War Department. He told her she might receive a call and, after a couple of weeks, she did. She was soon receiving intensive training at the "Farm" (later used, famously, as CIA training grounds), and working with other agents, all of whom knew each other only by their agent names. Aline's was Tiger.

|

| Aline on just another weekend in the country |

Aline's entrée was her contact, Eduardo, aka Top Hat, who was a foppish regular in society and the clubs around town––not to mention, a kleptomaniac. He had a large collection of jewelry and other gewgaws that he'd lifted from his society friends. Soon after her arrival in Madrid, Aline was spending evenings at society dinner parties, at nightclubs with one of the country's most popular bullfighters, and weekends at the country estate of Count von Fürstenberg, and his wife, the drop-dead gorgeous Gloria.

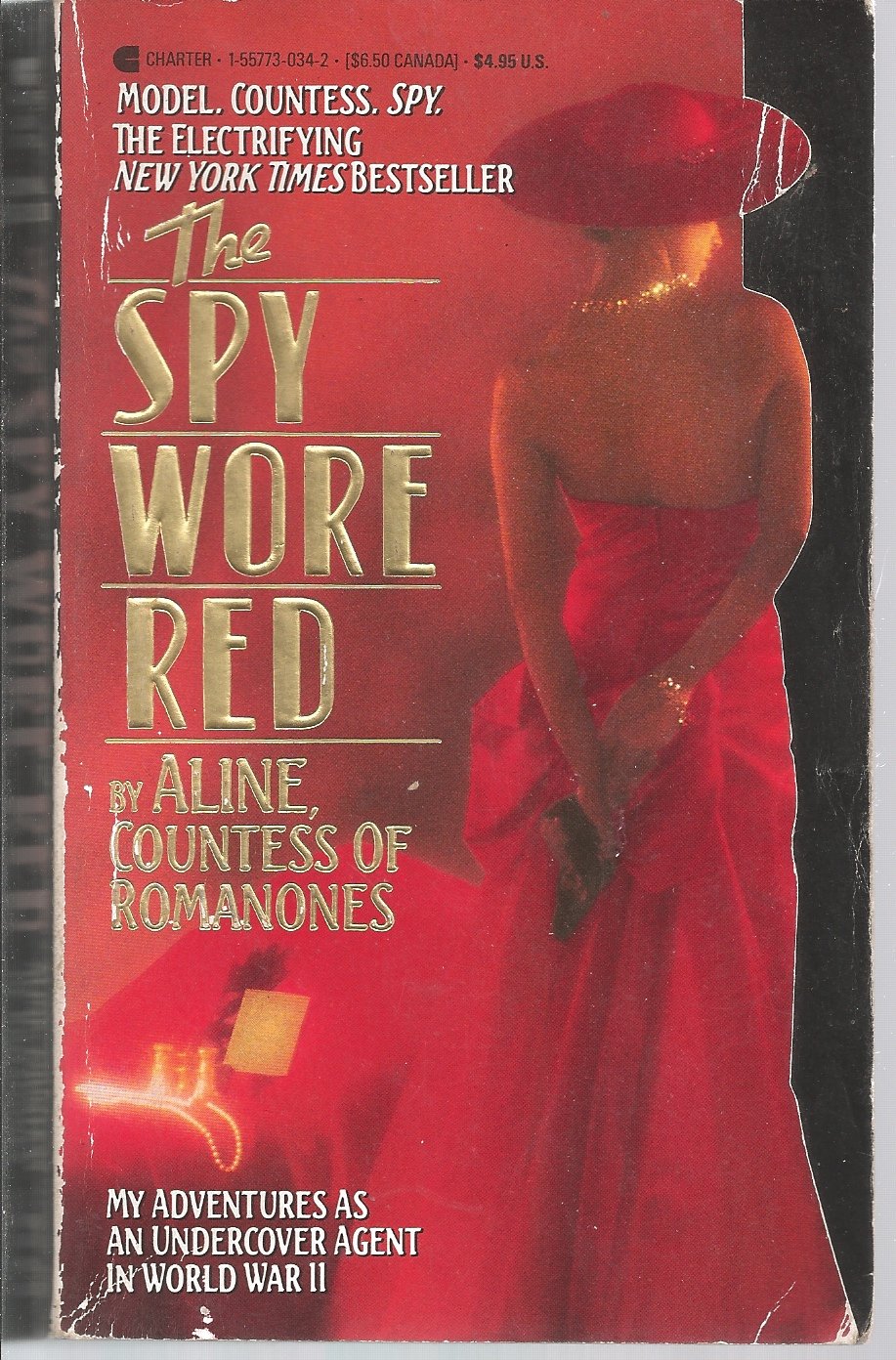

|

| Aline, licensed to kill |

Aline reports that on her very first day in Europe, she's taken to a casino in Estoril, in Portugal, where she almost literally stumbles upon a man in full formal evening wear who has just been murdered with a stiletto. Quite an introduction to one's first spy assignment! And people were forever sneaking into Aline's room to tell her she was the only one they could contact with vital information to pass on to the American government. Seriously? A 20-year-old girl who was supposed to be a clerk at an office? Some of those confiding people ended up dead; some Aline claims to have unveiled as German spies.

Now, I take my World War II history very seriously, but this is one of those times I decided I just had to forget about my doubts and go with Aline's tale. Why? Because it's such a hoot, that's why.

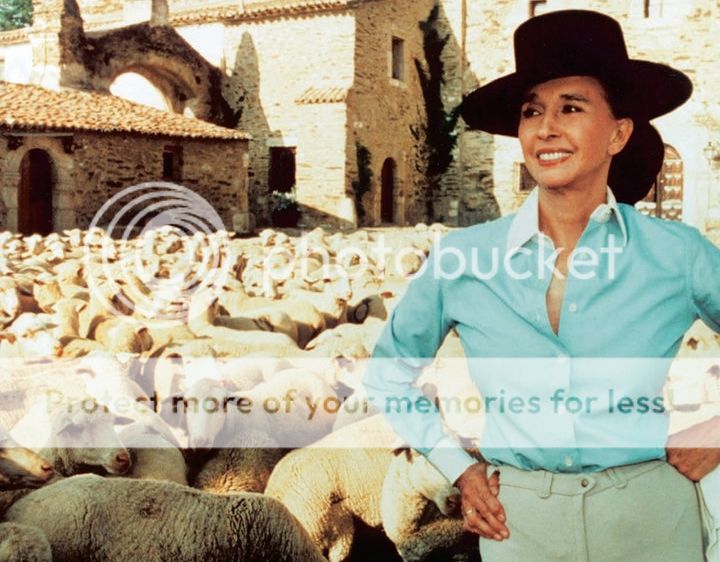

|

| I'm not sure what Aline's up to with all these sheep |

|

| I'd be laughing, too, Aline, if I had those rocks |

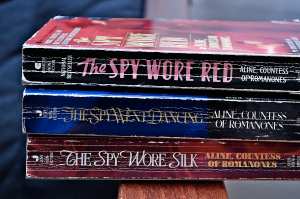

Now I have to go find Aline's follow-up books, The Spy Went Dancing: My Further Adventures As an Undercover Agent, and The Spy Wore Silk (with the same subtitle). Since Aline, born in 1923, is apparently still alive, who knows what other stories she may yet have to tell.

Aline was hardly the only woman whose memoirs describe using her position in the social world to observe the inner workings of Nazi operatives. And not the only improbable woman to be in that position, as a couple of other tales demonstrate.

You'd think it's never a bad time to be born a princess, but how about 1917 in St. Petersburg, Russia? That's when and where Marie Vassiltchikov came into the world. It's not surprising that she and her family left the country after the Bolshevik revolution. The family members wandered around Europe, and in 1940, Marie (usually called Missie) and her sister Tatiana moved to Berlin, where Missie's friends and her polyglot language skills got her a job at the German Foreign Ministry's Information Office, referred to in her memoir, Berlin Diaries 1940-1945, as the A.A., for its German short name, the Auswärtiges Amt.

Missie's timing in life sure is lousy, isn't it? She couldn't help when and where she was born, but you'd think she might at least have suspected that Berlin in 1940 wasn't the greatest choice. Still, her social life in Berlin was active and glittering, despite the war. Soirées and tea parties at various embassies and society friends' homes were a near-daily event, at least in the early part of the war. The amazing thing is to see all the nationalities of her friends: German, Russian, French, Hungarian, Bulgarian and several more, and the stunning array of titles.

Missie and Tatiana are no longer wealthy, so she does have to spend her days working. She's not crazy about some of the blowhards at the office, and wishes she could have taken the job at the American Embassy she was offered just days too late. She has access to lots of top-secret information and, one day, having been given by mistake a sheet of the special yellow-top paper reserved for particularly hot news, she decides to amuse herself with a made-up story that there had been riots in London, resulting in the king's being hanged at the gates of Buckingham Palace. She "passed it on to an idiotic girl who promptly translated it and included it in a news broadcast to South Africa." Oh, those girlish hijinks!

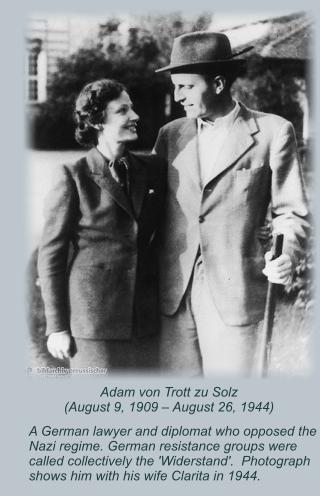

I shouldn't give the impression that Missie was just some ditzy dame with a useless title, though. While on the job, she met Adam von Trott zu Solz, an English-educated lawyer, with an American heritage (his grandmother was a descendant of John Jay, the first Chief Justice of the US Supreme Court). Trott was part of an active anti-Nazi group within the A.A., and he became Missie's boss. Missie's memoir doesn't reveal much about the group's activities, which resulted in the unsuccessful "July 20 Plot" to kill Hitler, but she clearly knew what was going on. She does describe her reactions and those of friends and family when many of the plotters were arrested by the Gestapo, including her visits to the Gestapo to plead on Trott's behalf until a sympathetic man there took her aside and warned her not to return. Soon afterward, Trott was hanged at just 35 years old, leaving a wife and two small children.

Probably the most riveting parts of Missie's memoir are her graphic descriptions of the air raids on Berlin, particularly the extremely destructive raids of November, 1943. She sees a young girl on top of a pile of rubble, picking up bricks, dusting them off and throwing them away. The girl's whole family is under the rubble. As Missie laboriously climbs over smoking ruins to get to work, she sees chalked messages on the walls of wrecked houses: family members leaving word in hopes they will lead to a reunion with their families and friends. When she is out with Tatiana, trying to locate friends, the streets are full of refugees, pushing their meager remaining belongings in baby carriages. Tatiana's favorite antique store is still burning, with the silks and brocades making for a "pink glow [that] looked very festive."

After Trott's execution, Missie thought it best to leave Berlin. She moved to Vienna and became a Red Cross nurse. While there, she met Peter Harnden, an American Army intelligence officer. Missie and Peter married in 1946, and the pair moved to Paris, where Peter became a successful architect. Missie was widowed in 1971 and moved to London, where she died of leukemia in 1978, leaving four children.

Alright, so we've got an American model as OSS agent and a White Russian aristocrat working in the German Foreign Ministry with anti-Hitler plotters. How about an even more unlikely inside observer of the Nazis and their allies? Bella Fromm, a Jew, was a society reporter who kept right on reporting on Berlin social life until she fled the country in 1938, several years after the Nazis came to power in Germany. How the heck did that happen?

Bella was a society columnist for the Berlin newspaper Vossische Zeitung. She became well-known in Berlin during the Weimar era, and was a regular at parties given in high society which, once the Nazis took over, became dominated by political figures. Her friendship with several politicians, and especially foreign members of the diplomatic corps, seems to have provided her with some protection. Still, she was savvy enough to send her daughter out of the country in 1934 and, while she continued to be invited to parties, her columns no longer appeared under her own name after the Nazis had been in power for about a year.

Fromm finally fled Germany for New York in 1938, where she published Blood and Banquets: A Berlin Social Diary in 1943. She begins with a description of her life in Germany before Hitler came to power, then with what she claims are her diaries for each year from 1930 to 1938, wrapping up with a epilogue of her last encounter with the Nazis.

Questions have been raised as to whether Fromm's memoir reflects actual contemporary diary entries or have been amplified with the benefit of hindsight. Either way, it's still fascinating––in the way watching a snake can be––to read about the cast of goons suddenly elevated to the heights of Berlin society. This reaches an absurd level in Fromm's description of a 1933 party during which the new Führer kisses her hand and makes small talk with her; of course, having no idea that she is Jewish.

Questions have been raised as to whether Fromm's memoir reflects actual contemporary diary entries or have been amplified with the benefit of hindsight. Either way, it's still fascinating––in the way watching a snake can be––to read about the cast of goons suddenly elevated to the heights of Berlin society. This reaches an absurd level in Fromm's description of a 1933 party during which the new Führer kisses her hand and makes small talk with her; of course, having no idea that she is Jewish.Books like these remind me that memoirs can be so much better than history books, or even novels, if you want to get that feeling of being a spy on history.