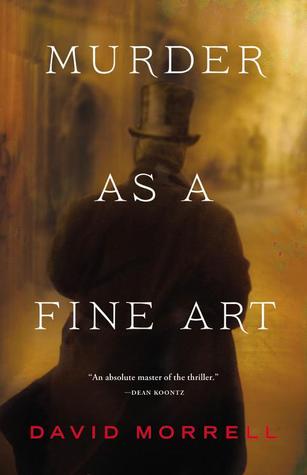

Murder as a Fine Art by David Morrell

Murder as a Fine Art by David MorrellIn the 1850s, laudanum, a tincture of opium, was available without prescription in England and used to treat everything. Pain, the common cold, the faintness women experienced from wearing corsets to make 18-inch waists and hooped skirts weighing 37 pounds to hide the movement of their legs. While a few doctors recognized that prolonged use of laudanum created a dependency, most people viewed its overuse as a failure of fortitude. Such a failing was a secret to keep behind the heavy curtains of a Victorian living room. It certainly was not to be made public, as Thomas De Quincey does in his shocking bestseller, Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Publication of his "On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts" did his reputation even more damage. In that series of satirical essays, he describes the two sets of Ratcliffe Highway murders, which terrorized England in 1811, as "the sublimest in their excellence that ever were committed."

In a city of almost three million, Detective Inspector Ryan and Constable Becker are part of a force of only 7,000 men. Violence in London isn't uncommon, but murder is rare and multiple murder almost incomprehensible. They conduct an investigation at a time when taking plaster casts of footprints and preserving a crime scene are new ideas, but fighting crowds who want to view the scene and assault suspicious strangers and foreigners, particularly the Irish, are old problems. It's critical not only for London, but the British empire, that this crime, which recalls the nightmares of 43 years ago, be solved quickly.

Ryan and Becker aren't nearly as well fleshed-out as the uninhibited De Quincey, a friend of Coleridge and Wordsworth, and the unflappable and resourceful Emily. The policemen serve mostly to reflect Victorian society in their attitudes about De Quincey's use of opium, his frank talk in front of Emily and Emily's modern bloomers and insistence on accompanying the men everywhere. They are bewildered by De Quincey's wish to analyze the crime by using Kant's ideas about perception and pre-Freudian ideas about the subconscious and memory. After a while, almost nothing De Quincey and Emily do can shock them.

I liked De Quincey and Emily and enjoyed the background story of the opium wars between China and Britain. I was fascinated by the rich description of Morrell's Victorian London. Sewage flows into the Thames, livestock roam the streets, Dr. John Snow only recently proved that cholera is caused not by breathing foul air but by drinking contaminated water. Touching patients is left to surgeons, who are lowlier than physicians. Lord Palmerston, Home Secretary and the country's most powerful man, is called Lord Cupid by people who live on the street. Fifty thousand beggars are ignored because if they're noticed, something should be done to help them. Every day at the Coldbath Fields Prison, prisoners climb 8,000 steps on a treadwheel to power the laundry facilities and "earn" food by spinning a crank in their cell 10,000 times to fill and then dump a cup of sand. (Clearly, the Victorians were into punishment rather than rehabilitation.)

I liked De Quincey and Emily and enjoyed the background story of the opium wars between China and Britain. I was fascinated by the rich description of Morrell's Victorian London. Sewage flows into the Thames, livestock roam the streets, Dr. John Snow only recently proved that cholera is caused not by breathing foul air but by drinking contaminated water. Touching patients is left to surgeons, who are lowlier than physicians. Lord Palmerston, Home Secretary and the country's most powerful man, is called Lord Cupid by people who live on the street. Fifty thousand beggars are ignored because if they're noticed, something should be done to help them. Every day at the Coldbath Fields Prison, prisoners climb 8,000 steps on a treadwheel to power the laundry facilities and "earn" food by spinning a crank in their cell 10,000 times to fill and then dump a cup of sand. (Clearly, the Victorians were into punishment rather than rehabilitation.)This is the London that Morrell, best known for his creation of Rambo in First Blood, brings vividly to life. There is plenty of action and suspense and a fair amount of graphic violence. The villain is psychologically interesting. I recommend Murder as a Fine Art, published on May 7, 2013 by Mulholland Books/Little, Brown, to people who enjoyed Caleb Carr's The Alienist, Michael Cox's The Meaning of Night, John Fowles's The French Lieutenant's Woman or Charles Palliser's The Quincunx. On my list of things to read, I'm putting De Quincey's "On Murder Considered as One of the Fine Arts" and The Maul and the Pear Tree: The Ratcliffe Highway Murders, 1811 by P. D. James and historian Thomas A. Critchley. It's sad to consider how unthinkable multiple murder was to 1811 London and how thinkable it is today.

I read this very entertaining book, and one fact is burned into my brain. The typical dose of laudanum was measured in drops. Although one ounce would kill most people, De Quincey drank 16 ounces of the stuff! My mouth dropped open after I checked the ketchup bottle in my fridge to remind myself what 16 ounces look like.

ReplyDeleteSo true, just shocking how much De Quincey was taking . I was also surprised to find that he is in his 60's and still alive, in the book.

ReplyDelete