It only makes sense that people who love crosswords would also love crime fiction. And that those addicted to games of strategy enjoy stories of detection. I really like books in which the characters themselves are involved in these games. It's a little like reading a novel in which there's another novel––characters playing games in mystery fiction create a Russian nesting doll of following clues or manipulating an outcome. If a naïve player is swept into a larger game of life and death––or assassination, as in the case of two characters below––goody, goody gumdrops.

It only makes sense that people who love crosswords would also love crime fiction. And that those addicted to games of strategy enjoy stories of detection. I really like books in which the characters themselves are involved in these games. It's a little like reading a novel in which there's another novel––characters playing games in mystery fiction create a Russian nesting doll of following clues or manipulating an outcome. If a naïve player is swept into a larger game of life and death––or assassination, as in the case of two characters below––goody, goody gumdrops. In Karen Engelmann's The Stockholm Octavo, Emil Larsson, a young sekretaire in Stockholm's Office of Customs and Excise, is such a player. He's somewhat oblivious and self-satisfied. His job involves uncovering smugglers and inspecting suspicious cargoes on the docks. In his off hours, he drinks and plays cards with people of all stations. This is helpful professionally, but it offends his supervisor. He insists Emil be married by midsummer or he'll be fired. Despite his best efforts, Emil cannot find a suitable woman; however, Mrs. Sofia Sparrow, seer and host of an exclusive gaming salon, envisions a golden path leading to love and connection in his future.

In Karen Engelmann's The Stockholm Octavo, Emil Larsson, a young sekretaire in Stockholm's Office of Customs and Excise, is such a player. He's somewhat oblivious and self-satisfied. His job involves uncovering smugglers and inspecting suspicious cargoes on the docks. In his off hours, he drinks and plays cards with people of all stations. This is helpful professionally, but it offends his supervisor. He insists Emil be married by midsummer or he'll be fired. Despite his best efforts, Emil cannot find a suitable woman; however, Mrs. Sofia Sparrow, seer and host of an exclusive gaming salon, envisions a golden path leading to love and connection in his future. This future will be guided by the eight cards Mrs. Sparrow lays out for Emil from her special deck of Octavo. The cards represent eight people. It isn't easy to identify these folks, but once Emil does, he may manipulate an event's outcome by "pushing" the eight. It is "destiny, partnering with free will." Needless to say, Emil is determined to complete his Octavo.

This future will be guided by the eight cards Mrs. Sparrow lays out for Emil from her special deck of Octavo. The cards represent eight people. It isn't easy to identify these folks, but once Emil does, he may manipulate an event's outcome by "pushing" the eight. It is "destiny, partnering with free will." Needless to say, Emil is determined to complete his Octavo.When Mrs. Sparrow takes possession of a gorgeous folding fan, more than Emil's personal future is revealed in the cards. For years, a beautiful and ruthless baroness, known to everyone as The Uzanne, has directed the flow of information in any given room with her fan. It's the perfect tool for a woman who wishes to participate in political games usually reserved for powerful men. Mrs. Sparrow, a strong supporter and friend of King Gustav III, sees Gustav's fate bound to the myths surrounding the famous fan and the cards of the Octavo.

|

| Karen Engelmann makes the subject of hand fans engrossing. Her website has information about them. |

I don't often think of books as delicious, but that is a fitting description for The Stockholm Octavo, Engelmann's historical fiction debut, published in 2012 by HarperCollins. Her game of Octavo and 1791 Stockholm are fascinating. It's a stratified society, with all classes coming to a boil as revolution sweeps Europe. Stockholm's lower classes are struggling to survive the winter. The police are corrupt and cannot be trusted. Ambitious upper-class women use every weapon society allows them as they connive for power, traditionally through marriage or social connections. Their dresses are amazing testaments to their privilege and the tailors' skills; their fans take many hours of practice to wield skillfully.

|

| Gustav III |

Even while he plots to rescue the French royal family, Gustav gives unprecedented privileges to commoners, and some members of the nobility are outraged. The King's efforts at modernizing Sweden and his government make them believe Sweden is going to the dogs. A group called the Patriots has formed to oppose Gustav, and his brother, Duke Karl, would like to replace him on the throne.

This is the Stockholm in which Emil moves to identify his Octavo's eight, and, through them, to fulfill his, and Gustav's, destiny. It is perfect bed or bathtub reading. Afterward, a nonfiction book about King Gustav III may be in the cards.

|

| Gustav's juicy life was the subject of a Swedish mini-series in 2001 |

If you play chess, you may know what a zugzwang is. As Ronan Bennett's Zugzwang tells us, the word is derived from the German Zug (move) and Zwang (compulsion, obligation). In chess, it means that a player has been reduced to "a state of utter helplessness." He is obliged to move, but each move only worsens his position.

If you play chess, you may know what a zugzwang is. As Ronan Bennett's Zugzwang tells us, the word is derived from the German Zug (move) and Zwang (compulsion, obligation). In chess, it means that a player has been reduced to "a state of utter helplessness." He is obliged to move, but each move only worsens his position.Of course, the condition of zugzwang isn't restricted to chess players, as narrator Otto Spethmann, a St. Petersburg psychoanalyst with "no time for political affairs," will discover during the course of this book.

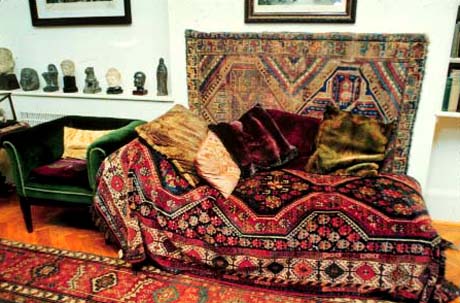

|

| The psychoanalytic couch |

All is going well for Spethmann––in fact, he is falling in love with Anna (yes, this is a no-no for our good doctor, but the smokin' sex scenes drive away regrets he might have)––until Mintimer Sergeyevich Lychev, a police detective, drops in to question him about the murder of Yastrebov. Lychev brushes off Spethmann's protests that he has no idea who Yastrebov is. Colonel Maximilian Gan, head of the secret police (Okhrana), is interested not only in Yastrebov, but in Spethmann's patients, Lychev warns. "I can understand you wanting to think this has nothing to do with you, Spethmann," Lychev says. "You would like it to be a game, the kind that children play and when they get frightened all they have to do is say I don't want to play any more. But this game is different and, like it or not, you are involved now. There is no way to stop other than to win or lose."

|

| This chess set is based on the French invasion of Russia in 1812. For more rare and exotic sets, see the book Chess Masterpieces. |

|

| This Soviet chess set from early 1900s features capitalists and proletariat |

Zugzwang was published in 2007 by Bloomsbury. If you play chess, you'll enjoy the pictures of Spethmann's chess board that reflect the moves he and Kopelzon make in their game, but you don't need to play chess to relish this captivating book that questions what a man must do when he finally cannot look away.

|

| Tsar Nicholas II with his family in 1914 |

No comments:

Post a Comment