Live by Night by Dennis Lehane

Live by Night by Dennis LehaneMamas, don't let your boys grow up to be gangsters. That is, if this book's opening quakes your bones:

Some years later, on a tugboat in the Gulf of Mexico, Joe Coughlin's feet were placed in a tub of cement. Twelve gunmen stood waiting until they got far enough out to sea to throw him overboard, while Joe listened to the engine chug and watched the water churn white at the stern. And it occurred to him that almost everything of note that had ever happened in his life––good or bad––had been set in motion the morning he first crossed paths with Emma Gould.It's the same Joe Coughlin, son of powerful Irish cop Thomas and younger brother of Aiden (Danny) and Connor, whom we met in Lehane's sprawling historical epic, The Given Day, set in 1918-19 Boston. While that 2008 book is about the Coughlins during a dizzying epidemic of flu, corruption, and striking police, Live by Night is all about handsome Joe, although his father appears and Danny drops in briefly. Joe was conceived in an effort to fill the hole at the center of his family, a chasm between his parents, and between them and the world at large. Rather than filling, the hole found its center in lawless Joe. Yet, despite Joe's refusal to heed his father's warnings or to obey the rules, he is the most open of Thomas's three sons, with a heart you can see "through the heaviest winter coat." Joe is an immensely conflicted and appealing young man. He lives for "moments in a world without nets––none to catch you and none to envelop you." Joe knows he'll probably die young. And now, here he sits, not yet 30, hands tied and feet encased in cement, while Lehane takes us back to watch the trajectory of Joe's career from rebellious outlaw to gangster prince.

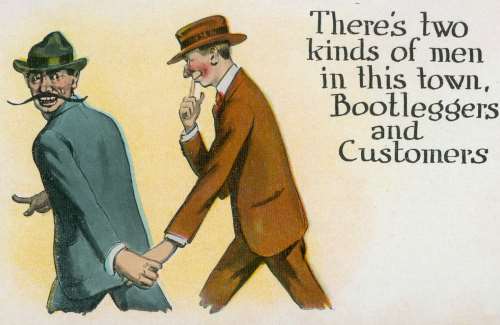

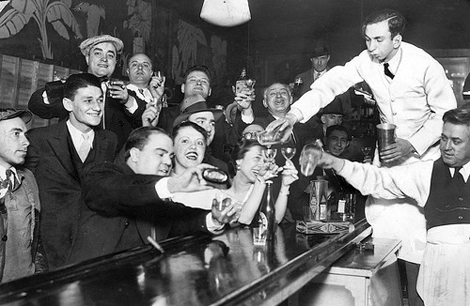

It's 1926, and Prohibition is in full force. Mobs––split down ethnic lines of Italian, Jewish, and Irish––control illegal activities such as gambling and supplying alcohol. While most mobs deal in whiskey, the Hickey and Pescatore gang handles rum. They've cornered the market on sugar and molasses imported from Cuba into Tampa, Florida, where the alcohol is distilled and driven up the Eastern Seaboard in midnight runs.

It's 1926, and Prohibition is in full force. Mobs––split down ethnic lines of Italian, Jewish, and Irish––control illegal activities such as gambling and supplying alcohol. While most mobs deal in whiskey, the Hickey and Pescatore gang handles rum. They've cornered the market on sugar and molasses imported from Cuba into Tampa, Florida, where the alcohol is distilled and driven up the Eastern Seaboard in midnight runs.Nineteen-year-old Joe comes across Emma when he and the Bartolo brothers rob a gaming room in a South Boston speakeasy. Until then, they had stuck to petty crimes. Had they known the speakeasy belonged to prominent mobster Albert White, they might have run as far as their legs would carry them. The stickup is a mistake. Joe compounds that error by losing his head over Emma, whose eyes, "pale as very cold gin," fit a young woman who hails from Charlestown, where "they brought .38s to the dinner table, used the barrels to stir their coffee." Emma is White's mistress.

White doesn't like being robbed, and he likes competition for Emma even less. He takes advantage of a bank heist's disastrous aftermath to vent his rage on Joe; however, White's actions take a backseat to those of Joe's father, Deputy Police Superintendent Thomas Coughlin. Like Lehane's series protagonist Patrick Kenzie, Joe has old grievances with his dad. Father-son issues––the limits of loyalty, the consequences of violence, and the nature of betrayal––provide the backdrop as Joe is incarcerated in Charlestown Penitentiary, "a dumping ground, and then a proving ground, for animals." There, Joe finds another father figure in imprisoned mob boss Thomaso "Maso" Pescatore, who runs his bootlegging operation from behind bars and directs Joe to Florida upon his release.

|

| Before radio and mechanization, Ybor City cigar factory workers listened to someone reading aloud. |

As the end of Prohibition approaches, the global economy is worsening. People need hope, as well as jobs, but they've often had to settle for a drink. When alcohol becomes legal, then what? While the world is changing, Joe has always believed people don't really change. Yet, he and Graciela have already started to live by day, "where the swells lived." How do good works follow bad money?

Questions such as this one arise from Lehane's examination of faith, love, redemption, and revenge, and the role luck and fate play in human destiny. Early on, Joe tells his father that there are no rules but the ones a man makes for himself. Joe is a fascinating character due to his evolving interpretation of events, assessments of people, and understanding of himself over a decade. Clear prose and depth of characterization are Lehane trademarks, and following Joe is a treat. Unlike others who stayed on top in the rackets, Joe isn't known for having amputated his conscience. He's the kind of mobster who hopes he won't have to kill his best friend, but that's not to say he won't; he simply won't do it for reasons of greed. Joe's father Thomas Coughlin, Maso Pescatore, and best friend Dion Bartolo also develop; however, there's something unknowable about the book's three beautiful women. Perhaps it's because Joe doesn't really understand them, even though he realizes why the nuns rail against the sins of lust and covetousness, which can "possess you surer than a cancer," and "kill you twice as quick." I found the idealistic Graciela less interesting than the two more complex women: enigmatic Loretta Figgis, beautiful daughter of Ybor's Chief of Police Irving Figgis, and the inscrutable Emma Gould, behind whose pale eyes "lay something cold and caged . . . in a way that demanded nothing come in."

The tone and pace change from noirish suspense to a slower ending, suitable for its tropical location, but a little languid and mushy for my taste. No matter, Dennis Lehane has written a gangster novel, captivating for its characters and philosophical questions and moving in its bittersweetness, vividly set during Prohibition. The Coughlins aren't a Mafia family like the Corleones, but one can hope to see them vault from book pages onto the movie screen. I've heard that director Ben Affleck is interested. I've also heard that Lehane may make these two books into a trilogy, and my pulse does a rumba thinking about this.

Note: Dennis Lehane's Live by Night was published earlier this month by Morrow/HarperCollins. It isn't necessary to read The Given Day first, but a reader loses by not doing so. Now is the perfect time. The World Series is just around the corner, and baseball is one of The Given Day's pleasures. Be sure to close with Live by Night.

No comments:

Post a Comment