I hate housework. Not with a seething, white-hot hatred or a disdain so profound that I refuse to do any house cleaning, but I do admit that my primary motivation when I clean is to avoid embarrassment if a neighbor drops in. Though, if somebody comes by when things look particularly bad, I could always pull a Phyllis Diller and say: "Who could have done this? We don't have any enemies."

Phyllis Diller (may she rest in peace) also wisely said: "Housework can't kill you, but why take a chance?" Now that I think about it, though, Erma Bombeck's reply to Diller was that if you do it right, housework

can kill you. As a mystery reader, I'd put a slight twist on that and say that housework done

wrong can kill––somebody. (

Warning: spoilers of a couple of well-known classics are included in this post.)

In 1960, Peg Bracken wrote

The I Hate To Cook Book. Bracken was clearly a mystery lover; she includes a recipe for Nero Wolfe's eggs, and a slow-cooking stew recipe for those days when you want to abandon household chores and stay in bed reading a good murder mystery. But no matter how much she hated to cook, Bracken didn't kill anybody with her cookery––unlike some people.

In Dorothy L. Sayers's

Strong Poison, Lord Peter Wimsey struggles to clear Harriet Vane of murdering her former lover, Philip Boyes, with arsenic. Wimsey's challenge is to figure out how anyone other than Harriet could have slipped the arsenic to Boyes, whose last meal was one in which he shared all the food and drink with his cousin. The answer to Wimsey's challenge: a clever and deadly way of making an omelet.

Nine years after the publication of

Strong Poison, Agatha Christie penned a new Hercule Poirot book, called

Sad Cypress, that seems to have been inspired by the earlier Sayers book. Christie's main character is a young woman in the dock for murder by poison when a man falls in love with her and is determined to save her by proving her innocence. As if that's not similar enough to

Strong Poison, the man's name is Peter Lord! Beyond those similarities, the stories are very different, though. Christie's sleuth is, of course, Hercule Poirot, not Peter––and a good thing, too, since Christie's Peter seems to have only a fraction of the little grey cells of Poirot or Wimsey.

In Roald Dahl's short story, "Lamb to the Slaughter," Mary Maloney is a pregnant housewife whose police detective husband, Patrick, comes home from work and tells her he's leaving her. In a state of shock, Mary goes through the motions of dinner preparation. When she brings a large, frozen leg of lamb into the kitchen, Patrick tells her not to bother, as he's going out. His disdain jolts Mary from shock to outrage and she whacks him with the leg of lamb, killing him.

Clever Mary then puts the lamb into the oven, heads off to the grocery store to give herself an alibi and then goes home to "discover" the body. The murder is investigated by Patrick's work friends, who never suspect Mary and spend their time looking for the blunt object that obviously killed Patrick. When they point out that the roast seems to be finished, Mary invites them to eat it. As they eat, one detective remarks that the murder weapon is probably right under their noses. Too right!

In

Busman's Honeymoon, the last of the Lord Peter Wimsey books, Dorothy L. Sayers shows a preoccupation with the perils of housekeeping. When Lord Peter and his new bride, Harriet, arrive at Talboys, the old house they've purchased in the village Harriet knew as a girl, they are surprised that nothing has been done to ready the place for them, as had been agreed. Bunter and the next-door neighbor, Mrs. Ruddle, have to hurry to clean up, prepare the beds and light the lamps and the fire.

The next day, a recalcitrant chimney blocked with "sut," as Mr. Puffet the chimney sweep calls it, causes a domestic disaster. Wanting to be helpful, the vicar fires a shotgun up the chimney to knock out the blockage, which has the effect of causing an avalanche of dead animals, bric-a-brack and clinkers to crash to the hearth and a gigantic cloud of ash to choke the room. More cleaning required! The day goes from bad to worse when a trip to the cellar on a domestic errand results in an unpleasant find: the corpse of the house's previous owner.

Housework even plays a role in the solution to the crime in

Busman's Honeymoon. That chimney mishap dislodges a clue, and it turns out that a regular domestic chore is the key to the ingenious murder method. If only a regular domestic chore around my house was integral to something really important. But I suppose cleanliness is its own reward.

Agatha Christie seemed to find an additional reward. She said the best time for planning a book is while you're doing the dishes. I guess I'll just have to take her word for it. I do my best thinking while mowing the lawn, but then I do that while sitting on a tractor. And, as Roseanne Barr used to say, when Sears starts selling a riding vacuum cleaner,

then it'll be time to start cleaning house.

Joan Rivers said she hates housework because you make the beds, you wash the dishes and six months later you have to start all over again. Another woman who hates housework is Judith Singer, the Long Island housewife protagonist of Susan Isaacs's first novel,

Compromising Positions. Though Judith's inconsiderate husband, Bob, definitely deserves a leg of lamb to the back of the skull, Judith channels her frustrations elsewhere. She investigates the murder of her periodontist, in the process discovering the seamy underbelly of suburbia. An entertaining book was made into an equally delightful movie, starring Susan Sarandon, Raul Julia, Edward Herrmann and Judith Ivey.

Did I mention I hate gardening too? I believe in the old saying that a garden is a thing of beauty and a job forever. Weeding is the most boring, back-breaking job ever. And why is it that it's so hard to pull weeds, but if I accidentally grab a real plant, it pops right out? My favorite thing about winter is that all the snow on the ground makes my garden and landscaping look just as good as my neighbor's.

Our British friends love their gardening, though, and it plays a role in many of their mysteries. In the Christie book I mentioned above,

Sad Cypress, the resolution is helped along by a knowledge of rose varieties. (Good thing I wasn't on the case.)

In Reginald Hill's

Deadheads, Inspectors Dalziel and Pascoe investigate a series of deaths at the Perfecta Porcelain corporation. Dalziel's old friend, Dick Elgood, an executive at the company, is convinced that its accountant, Patrick Aldermann, is bumping off people to clear a space for his own advancement. Aldermann is an avid rose gardener, who learned all about deadheading roses to make way for more vigorous growth from his great-aunt when he was only a boy. Has he taken the lesson too much to heart?

Even if you skip the hard work of grubbing in the dirt and just appreciate flowers through a visit to London's annual Chelsea Flower Show, that might not be safe enough. In

Chelsea Mansions, the eleventh in Barry Maitland's Brock and Kolla police procedural series, Nancy Haynes's dream of coming from the US especially for the show ends violently when, heading back to her hotel after her first afternoon's visit, she is suddenly and inexplicably picked up by a passerby and thrown in front of a bus, killing her. A few days later, a wealthy Russian émigré is killed in his garden. His house is right next door to the small, somewhat rundown hotel where Nancy Haynes had been staying. Are the two deaths connected?

After reading these books, I feel I've been warned off flower gardening and flower shows. I still remember that classic of Catherine Aird's,

Passing Strange, in which the village of Almstone's nurse, Joyce Cooper, is strangled at the Horticultural Society Flower Show.

Other garden produce gets into the act in G. M. Malliet's

Wicked Autumn, when that battle-ax Wanda Batton-Smyth, head of Nether Monkslips Women's Institute, is bumped off in the middle of the fall Harvest Fayre. I suppose Robert Barnard's

Fête Fatale is evidence that it's the gathering, not the gardening, that's the problem. After all, the church fête that is the scene of this book's murder of the new vicar is more about bric-a-brac and baked goods than produce and flowers. But, as with housekeeping, I'm not taking any chances.

As we head into the weekend, I think I'll take a page from Peg Bracken's book and throw something in the slow cooker while I curl up with a good mystery book.

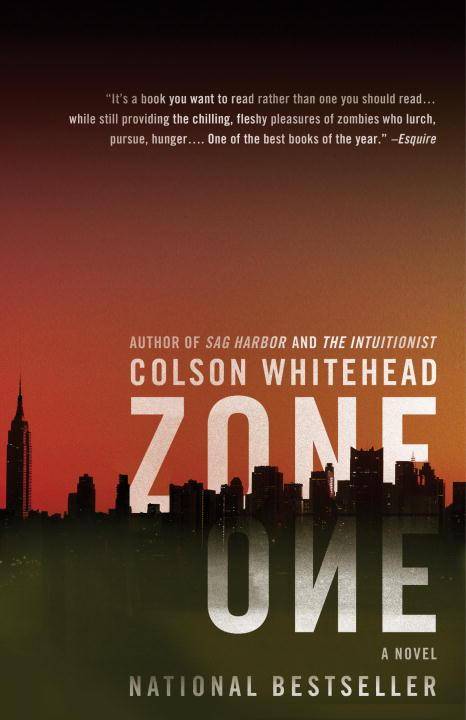

Zone One: A Novel by Colson Whitehead

Zone One: A Novel by Colson Whitehead